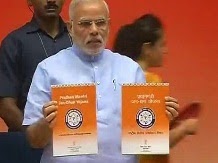

The Indian Government may have found its way into record books last week, when 1.5 crore bank accounts were opened on a single day through financial camps set up in 77,000 locations. Following through on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s I-Day promise, the Government put its financial inclusion programme into action last week. Its mouthful of a name — the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana or PMJDY involves opening bank accounts, aimed at the poor, whether rural or urban.

Only 58 per cent of Indian households have access to banking services. So the PMJDY’s target is to open 7.5 crore bank accounts by January next year. Under the programme, people will be able to open zero-balance accounts with any bank, either public or private.

The Jan Dhan scheme has much simpler Know-Your-Customer rules. An Aadhaar card is proof enough to open your Jan Dhan account on the spot. Attested NREGA cards, voters’ ID card are the other documentary proofs that are allowed. For those who don’t possess even these, simplified rules regarding proof of identity and address allow opening a more basic account.

The scheme offers a couple of freebies too. Accident insurance of up to ₹1 lakh comes free with each account. Those opening accounts before January 26 next year will also get life cover of ₹30,000.

Once operative for at least six months, holders may also be offered an overdraft facility, first for ₹2,500 and then for ₹5,000. Each accountholder will bag a RuPay debit card and will be able to access a basic form of mobile banking.

Right now, most Indian households rely on usurious money-lenders for credit and on the Saradhas and Saharas for their savings needs. Bank accounts for all may solve this problem. If bank accounts become the norm, it will also be easier for the Government to directly pay all subsidies into the accounts of the poor, instead of dispensing them through the vast, leaky network of government agencies. But who’s going to foot the bill, sceptics ask. The premium on accident insurance will be borne by the National Payments Corporation of India. But it cannot also pay the life insurance benefit tacked on at the last minute. In that case, the government’s go-to pawn, the Life Insurance Corporation, may be roped in. There is also the question of how banks will service these accounts once they’re operational. Will banks be interested in providing good service if the account is zero-balance? While the Centre has promised to ‘reimburse’ the costs, the quantum and mechanics of compensation are unclear at the moment.

Easy access to the banking system (and freedom from scam-artists and moneylenders) can materially lift India’s economic prosperity. Direct subsidy transfers can save money now lost in leakages. But that’s the long-term story. The costs of the Jan Dhan Yojana are front-ended.

If the Government takes on all the costs, this will be another welfare scheme to be funded by the tax payer. If insurers or banks end up footing some of the bill, they may pass it on to you.

As sheer numbers go, the scheme has started off with a bang. But the question is whether these accounts will actually generate the promised ‘Dhan’ for all those who have signed up for it.

What is it?

Only 58 per cent of Indian households have access to banking services. So the PMJDY’s target is to open 7.5 crore bank accounts by January next year. Under the programme, people will be able to open zero-balance accounts with any bank, either public or private.

The Jan Dhan scheme has much simpler Know-Your-Customer rules. An Aadhaar card is proof enough to open your Jan Dhan account on the spot. Attested NREGA cards, voters’ ID card are the other documentary proofs that are allowed. For those who don’t possess even these, simplified rules regarding proof of identity and address allow opening a more basic account.

The scheme offers a couple of freebies too. Accident insurance of up to ₹1 lakh comes free with each account. Those opening accounts before January 26 next year will also get life cover of ₹30,000.

Once operative for at least six months, holders may also be offered an overdraft facility, first for ₹2,500 and then for ₹5,000. Each accountholder will bag a RuPay debit card and will be able to access a basic form of mobile banking.

Why is it important?

Right now, most Indian households rely on usurious money-lenders for credit and on the Saradhas and Saharas for their savings needs. Bank accounts for all may solve this problem. If bank accounts become the norm, it will also be easier for the Government to directly pay all subsidies into the accounts of the poor, instead of dispensing them through the vast, leaky network of government agencies. But who’s going to foot the bill, sceptics ask. The premium on accident insurance will be borne by the National Payments Corporation of India. But it cannot also pay the life insurance benefit tacked on at the last minute. In that case, the government’s go-to pawn, the Life Insurance Corporation, may be roped in. There is also the question of how banks will service these accounts once they’re operational. Will banks be interested in providing good service if the account is zero-balance? While the Centre has promised to ‘reimburse’ the costs, the quantum and mechanics of compensation are unclear at the moment.

Why should I care?

Easy access to the banking system (and freedom from scam-artists and moneylenders) can materially lift India’s economic prosperity. Direct subsidy transfers can save money now lost in leakages. But that’s the long-term story. The costs of the Jan Dhan Yojana are front-ended.

If the Government takes on all the costs, this will be another welfare scheme to be funded by the tax payer. If insurers or banks end up footing some of the bill, they may pass it on to you.

The bottomline

As sheer numbers go, the scheme has started off with a bang. But the question is whether these accounts will actually generate the promised ‘Dhan’ for all those who have signed up for it.

Comments

Post a Comment